Ending the Behavior

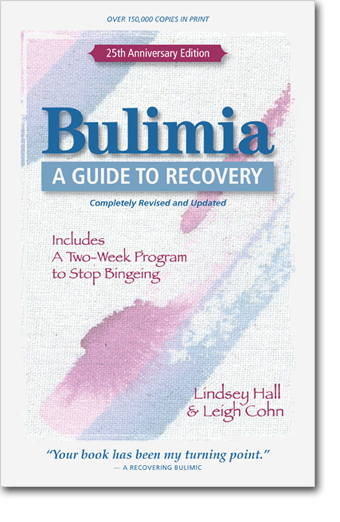

Excerpt from Bulimia: A Guide to Recovery 25th Anniversary Edition

In a tearful, emotional outburst, I described my bingeing and vomiting. At first Leigh didn't think it was a serious problem because he had never heard of such a thing. Besides, he had been a sweet-freak all his life, able to eat huge amounts of doughnuts and cookie dough without feeling guilty, gaining weight, or even getting cavities! His family loved big meals and boxes of candy. He assumed that I was just a sweet- freak, too, and threw up because I felt guilty about it. As I described the size and frequency of my binges, however, he could tell that something deeper was going on and that this was no ordinary problem. He listened to me that first day with love and compassion and said that he would try to help me.

In the past, I expected to get better "tomorrow" after one last binge. But this time I knew that I had to start taking definite steps. I made two resolutions. I would be absolutely honest by telling Leigh about all binges, and I would do anything to recover—even admit myself to a sanitarium, if necessary. At that time, there were no treatment facilities specifically for eating disorders, and this threat conjured up scary, melodramatic images I definitely wanted to avoid. Leigh promised to stick by me as long as I stayed committed to my recovery. He would help me come up with ideas about what actions I could take, listen, support, laugh, and love me; but we acknowledged that it was my responsibility to understand and overcome the behavior.

I went to see a psychiatrist primarily because of the tension and guilt I felt living with Leigh while still being married to Doug. I didn't mention my bulimia at first, but when I did, he recommended I see a woman psychiatrist who treated anorexics. I met with her once, but didn't feel comfortable. I realized the importance of confiding in someone, though, and decided to continue working on my recovery with Leigh.

Without any guidelines to help us, we brainstormed ideas. I began meditating twice a day and recommitted to journal writing. I tried to establish a better frame of mind by constantly watching what I was thinking and saying, and I consciously reframed negative "self-talk" to be more positive. I wanted to feel more relaxed, so I took walks and listened to my favorite music. I decided to drink a set amount of water each day, but I had difficulty with that, so I revised my expectations rather than feel like a failure. Also, Gürze Designs took off and required hours of concentrated sewing, during which I talked to myself about my recovery—sort of self-therapy!

I made lists: immediate goals, future goals, "Poor-Lindsey" and "Lucky-Lindsey" lists, what I liked and disliked about myself, reasons for wanting to get better, how I felt about my parents, my siblings, my life, ways to handle difficult feelings, and many others. I prepared a checklist of things I could do if I was on the verge of a binge, like exercising, sewing, gardening, soaking in a hot bath, and talking to Leigh or another friend about my feelings. Frequently I struggled, but increasingly I was able to overcome the urge to binge.

I had to approach food in a new way. In fact, it became my teacher because the way that I treated food was a lot like how I treated myself. If food were unimportant, expendable, not worth treating with kindness, then neither, I thought, was I. So, rather than labeling foods as "good" or "bad," which gave them power over me, I wanted to learn to eat anything—without fear.

One extraordinary step I took had a tremendous impact on my confidence, but I would not have attempted it alone. No one recovering from bulimia should do something like this without support and supervision. I went on a planned, all-day binge with the intent of not vomiting. I wanted to know, at a deep level, that I could eat anything—that I could have power over food.

On the big day, Leigh and I woke up to a bag of malted milk balls on the bedside table to start. We bought a pound of candy, a dozen doughnuts, caramel apples, caramel corn, a batch of homemade cookies, brownies, and drinks—all to take with us while delivering dolls in San Francisco. During the course of the day, we also ate hamburgers and fries, milkshakes, a greasy meal of fish and chips, and continuously snacked on white chocolate.

By bedtime, we were both exhausted and stuffed. Leigh felt sick, but I was preoccupied by how my body looked and felt—pregnant and unable to lie down comfortably in any position. Leigh would not let me out of his sight for obvious reasons. Without a support person, I would surely have vomited. In spite of stomach cramps, I was actually quite proud of myself at the end and laughed at what I had accomplished.

The next day, I had vowed not to eat until I felt hungry, and that didn't happen until nightfall. Also, I was sure I had gained weight, but I hadn't, and that made me even more confident. This was a real turning point for me—I knew I could reach a goal, and I had power over food instead of food having power over me.

For many months, I ate mostly foods that I had formerly considered "safe," like yogurt and bananas or cottage cheese and pineapple juice, but I tried to stick to three meals a day with small snacks in between. Eating that often seemed like a lot at first, but I was determined to stick to my plan even if I began to gain weight. Actually, I took a hammer to my scale after writing it a farewell note, so that I would not know what I weighed. Never again would I be ruled by a number.

I wanted out of any prison that existed for me. Toward that goal, I decided to allow myself one "forbidden" treat daily without guilt. This was a completely different orientation for me and was surprisingly easy. I began to treasure that one treat, which was a lot different than bingeing. I acquired likes and dislikes of certain foods and learned to say "no" by saying it to food. I began to pay attention to how I was eating and slowed myself down. Sometimes I had soothing music in the background during meals, and silently affirmed that eating in a healthy way was an act of loving kindness towards myself. This was fundamental, because I had treated myself so poorly for so long.

I tried to change my ideas of what I thought I "should" eat to what my body actually craved by becoming aware of internal hunger cues, which I had ignored for years. I started to try new foods. This was one of the hardest things that I had to do because I was so afraid of losing control. What I discovered, though, was that the more I restricted my eating to only specified foods, the more I wanted to binge. So I focused on improving my nutrition by eating healthier foods and becoming more balanced biochemically. When I took the time to go within and discover what it was that I was really hungry for, I experienced satisfaction and fullness. Sometimes what I craved wasn't even food! Doing artwork, saying something that needed to be said, or just sitting quietly, was sometimes more appropriate and more fulfilling.

Other times, I needed to scream into a pillow until I was hoarse or cry for hours on end. I released pent-up feelings, especially anger, by wrestling with Leigh on a large foam mattress on the floor and having exhausting fights with foam bats. We put on boxing gloves and he let me hit him. He always pulled his punches, but came very close to my face several times. I took long saunas. All these things had a settling effect on both my body and mind.

I began to explore spiritual issues outside the church I had attended as a child. I read books on different religions and discovered many wonderful spiritual teachers whose lives inspired me to be more loving towards myself and others. Along these lines, I kept a picture of myself on my dresser beside a candle and some flowers to remind myself that I was a good person, worth taking care of. I learned specific exercises that showed me how my values and beliefs were influenced by my parents, my childhood, and the culture in which I lived. Taking all these things into account enabled me to discover the truth of my own heart so that I could live in accordance with who I was at the deepest level of my being. This was real nourishment.

My most difficult commitment was to tell the truth all the time. I started by sharing my secrets about bulimia with the people I least wanted to. Doug, who had finally accepted our separation as permanent, was astounded, but took my finally confiding in him as an act of genuine caring. He said he didn't know why he hadn't asked me about spending so much time in the bathroom, and he was saddened by what I had gone through. At that moment of truth telling, I think we were closer than we had been in years.

About a month later, I began to write letters to people, with the option to send them or not. I wrote to my parents about how I felt when I was around them. I described my recovery, but did not ask for, expect, or receive much participation. I began to confide in friends, most of whom were interested, sympathetic, and supportive, though a few dropped out of my life. I wrote the following in a letter to my childhood friend, the one who had eaten all those oranges at boarding school: Finally, I can tell people about eating and throwing up. Do you know how ashamed I have been all these years, thinking I was abnormal and disgusting?

Gradually, I grew more comfortable with just being myself. I had always been desperate to maintain an image of unfailing perfection and independence, but now I stopped hiding shyness, opinions, and fears. As I grew to understand who I was and why, I also understood how well the bulimia had served me. It had been my friend, my buffer, my security, and my expression when I knew no other. It had been a way to anesthetize my overwhelming feelings, a vehicle for protesting my place in my family, and somewhere to hide when I didn't want to participate in life. As an addiction, though, it allowed no other behavior but itself and had completely consumed me. I fought hard to get me back!

During the first few months of recovery, I did binge many times, but these slips became less and less frequent until, after a year, they dwindled to one every couple of months. When I occasionally binged, Leigh and I had long talking and planning sessions, and I was able to think of those slips as a way to learn. I gradually accepted that a single binge did not return me to square one. Instead, it was a red flag signaling that I needed to examine why I relapsed and what I could do the next time to intervene. This level of compassionate acceptance, coupled with a firm commitment, was just the approach I needed. The episodes stopped completely after about a year and a half, after which Leigh and I wrote our booklet, Eat Without Fear. It has now been over 30 years since I quit.

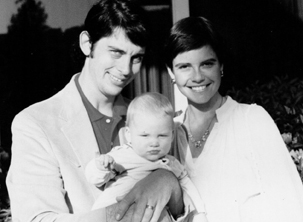

Family portrait 1980, the year Eat Without Fear was published